An American Holly in winter. Source: PennLive An American Holly in winter. Source: PennLive By Bailey Kozalla, Watershed Specialist With the start of the winter season, much of the landscape throughout Northwest Pennsylvania has lost most of its color. Despite this, glimpses of glossy green leaves and red berries are often seen scattering the bottomlands, a signature of the holiday season. The American Holly (Ilex opaca) is easily identified in the winter months against the contrast of a snowy scene. Inhabiting the understory of forests in moist soils, the tree normally grows between 15 to 25 feet tall but can reach heights of 60 feet. Its stout, stiff branches equipped with spine-tipped leaves is considered the hardiest broadleaf evergreen by many. Female plants possess its notable red berries which are an invaluable food source for wildlife species (but are poisonous to humans). The tree's beauty and hardiness makes it a desirable native ornamental. There are over 1,000 native and non-native varieties of the species - before planting, make sure to check with a nursery to ensure you are receiving a native American Holly.

1 Comment

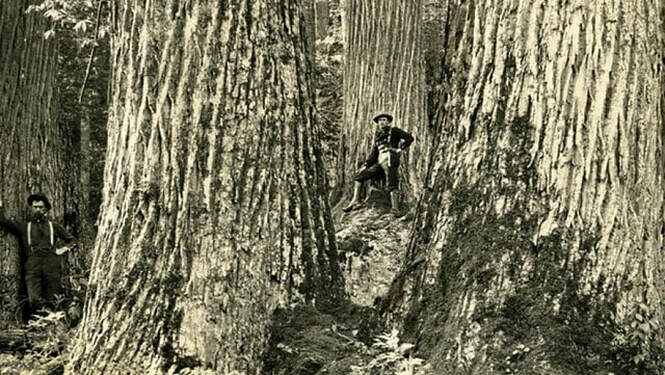

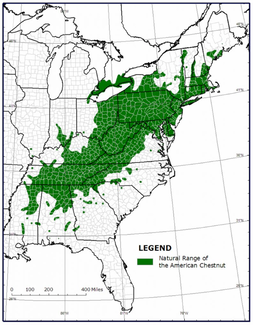

An American Chestnut stump sprout. The dead stem in the background succumbed to blight. The sprout will become infected with blight before it can begin to produce chestnuts. Source: Alliance for the Chesapeake Bay An American Chestnut stump sprout. The dead stem in the background succumbed to blight. The sprout will become infected with blight before it can begin to produce chestnuts. Source: Alliance for the Chesapeake Bay By Bailey Kozalla, Watershed Specialist Over a century ago, eastern hardwood forests looked very different than they do today. What once made up a quarter of deciduous tree species across its range has now been wiped away leaving little to no trace of its former existence. Now, the ghosts of over four billion individuals haunt our woods, and have since been a distant memory. The American Chestnut succumbed to a fungus known as chestnut blight or Cryphonectria parasitica. It was first discovered in 1904 at the Bronx Zoo and had since infected the chestnut’s entire range by 1950. The fungus forms cankers throughout the tree’s inner bark and eventually girdles the tree. Young American Chestnuts are often found stump-sprouting from ancestor trees, but they too will eventually die from the blight before they reach reproduction potential. The fungus resides in nearby oaks, which are notably unaffected. Despite these young chestnuts still being present in our forests, they are considered to be functionally extinct due to their inability to reproduce. As the chestnuts vanished, eastern forests were forever changed. The lumber industry lost a hallmark wood product that was known for its strong integrity and its ability to withstand weathering. In fact, many of the old fence posts seen on farm lands are made of chestnut wood. Additionally, many declining wildlife populations are attributed to the loss of the chestnut. The chestnut crop was a consistent annual food source for deer, squirrels, bears, turkeys, and others - unlike the oaks which only produce acorns every few years. Early 1900 reports document the steady decline of squirrel species, and several pollinator species who relied on the mid-summer bloom of chestnut flowers have declined or gone extinct. The present shrub-like chestnuts seen in the understory hardly resemble the ghosts of the “sequoias of the east” that dominated the landscape over one hundred years ago. There is hope, however, to see the return of chestnut trees to eastern forests. The American Chestnut Foundation began breeding blight-resistant trees with the naturally resistant Chinese Chestnut in 1989. This process continued over many years and resulted in a 94% American Chestnut and 6% Chinese Chestnut offspring. Doted the “Restoration Chestnut,” these trees are being experimentally planted throughout their historic range on federal, state, and private lands. Managers at the Allegheny National Forest are researching restoration techniques including site suitability, impacts of deer browsing, and the chestnut's response to prescribed fire. Research is still being done with regard to modern genetic modification in hopes to increase blight resistance even further. The regulatory process associated with reintroducing the blight-resistant chestnut will likely take many years, however. Despite the goal being to restore the tree to its native range, the chestnut will not likely be as dominant as it once was. This is due to the threat of invasive species and deer browsing which will make it difficult to encourage seedlings to become established naturally. This Halloween, remember that the ghost of the American Chestnut is a horror story of its own that haunts our eastern forests. Restoration efforts, however, are hoping that future generations of people, wildlife, and forests can enjoy the American Chestnut and the ecosystem services that it provides. The purple cone flower, like the ones pictured, are native to eastern and central North America. There are an herbaceous flowering plant of the genus Echinacea. They bloom from mid-summer through early fall.

There are nine species of Echinacea. Some species have been used for medicinal purposes. Native Americans use the roots as a traditional healing herb. Today the roots are used for herbal medicines. Two species are considered by the US Fish and Wildlife as endangered. They are E. Tennesseensis and E. Laevigata. The name “cone flower” is rooted from the Greek echinos which means “sea urchin”. Some Native Americans call them “elk root” because they observed that elk would seek out and eat the roots when hurt or unwell. We call them “cone flowers” because their petals are reflexed. At the Venango Conservation District offices, we planted purple cone flowers because they are a native plant. Our purpose was to provide wildlife food for our garden visitors. Butterflies and bees consume the nectar of our cone flowers, and in the winter, goldfinches eat up the seeds. Cone flowers also have network of root fibers so they can bind soil which protects against erosion. |

CATEGORIESs

All

Archives

July 2024

|